By Bill Adams

Bells and whistles, also known as chrome, glitter, and shiny stuff, is what manufacturers use to lure potential customers into their booths at national trade shows. Most do a good job doing so. After inducing potential customers to give their rigs a closer look, sales representatives usually expound on all the features, unique or proprietary, to their entire line of apparatus and not necessarily a particular rig being shown or one the purchaser may be interested in. Again, that’s their job. Some purchasers just look at the chrome and glitter on the whole enchilada rather than individual items that can affect firefighter performance, which in turn could make or break a fireground operation.

At regional and local shows, most of the rigs are already bought. They’re mostly from local departments, and some are even in service. Potential buyers have the opportunity to observe exactly what other people purchased and often get to ask the end user why something was specified. Hearing, “We’ve been using this for years and it really works!” or “That was a mistake!” can be beneficial to the purchasing process. Sometimes sales representatives without firematic experience can’t do the small stuff justice especially at national shows.

Commentators no longer in the fire service or apparatus industry can look at a single feature on a rig and jabber endlessly. We can be pro or con about a feature depending on our moods. Several personal observations follow from a local trade show with both perspectives. Purchasers should take multiple photos of rigs they’re looking at. Sometimes, you fail to notice something until you look at the pictures later. Unless noted, comments are my own and do not reflect the fire department’s reasoning for purchasing.

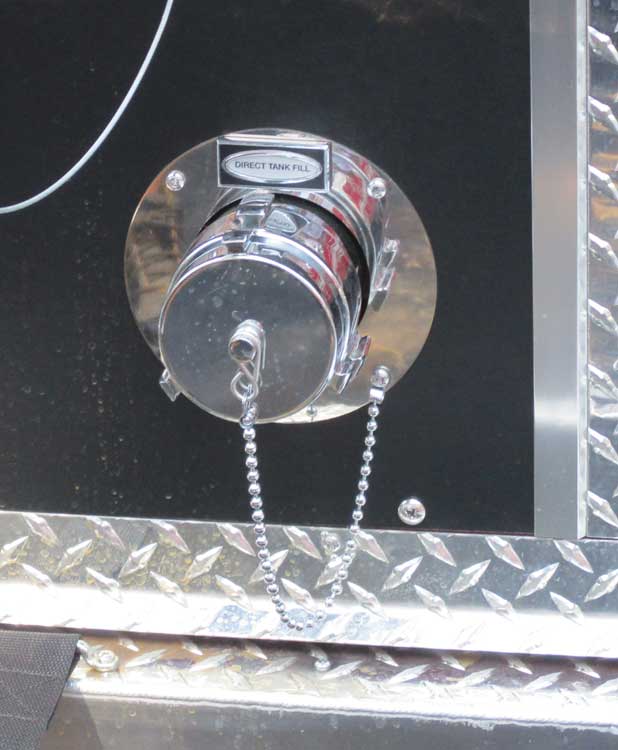

1. At first glance on the lower right-hand corner of this curb-side pump panel, it looks like there’s a 2½-inch gated auxiliary suction that’s obviously controlled at the operator’s panel. Pump operators control their own destiny.

2. A closer look at photo 1 shows it’s really a direct tank fill inlet, also assumedly controlled at the operator’s panel. A larger easier to read identifying label might prevent a rushed “Oops—wrong connection” that could prove embarrassing. It is unknown if there was a pressure gauge at the controller. Most tank manufacturers say the tank fill rate should not exceed a certain pressure. How come apparatus manufacturers don’t supply a pressure gauge as standard? Tank manufacturers should demand it.

3. This rig’s back end has a couple interesting features. First are the double vertical rollers on each side protecting the lower light assemblies from being damaged by the booster line. Usually there’s just one roller on each side. They might have busted some lights on their last rig. The second are the dual pull-out steps to access the direct tank fill and the rear discharge. It looks like it might be hard to balance yourself on the tailboard with that upper intermediate treadplate step below the hosebed (upper arrow), especially if the step is eight inches deep. The slide-out steps serving as mini work platforms make the hose humpers’ jobs easier.

4. Cowl (or grille) mounted mechanical sirens free up valuable front bumper space for the myriad equipment fire departments want to store there. Not every manufacturer allows grille-mounted sirens. The major reason for not doing so has been described as air flow to certain size motors. If engineers can put a man on the moon and bring him back, they should be able to design a grille to accommodate a mechanical siren (i.e. the “Q”).

5. A closer look at photo 4 shows what I call a winch receiver that’s flush with the front face of the bumper.

6. This front bumper on a heavy rescue rig has four receivers, two on the front and one on each side. The rig’s body has six other receivers strategically located. I was told they can be used for portable winches (if wired for such), tie-backs to double the pulling power of come-a-longs (grip hoists), and tie-off locations for rope rescue scenarios. Each can serve triple duty. With the multiple locations, there’s a good chance the rig does not have to be jockeyed around to position one for optimal use.

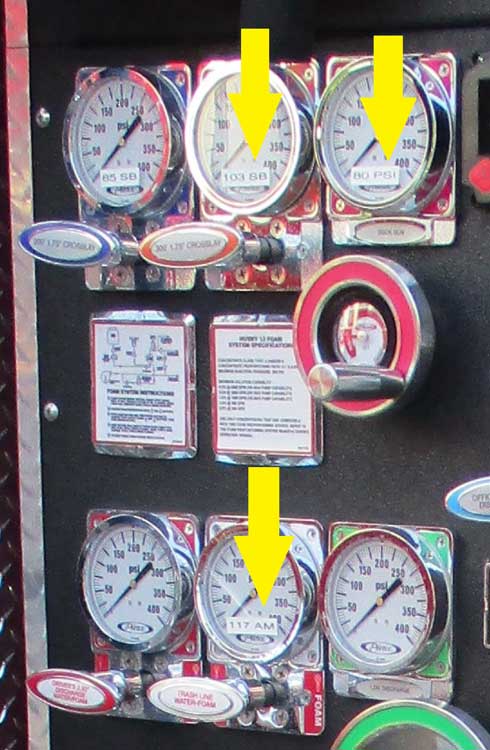

Starting in the late 1970s, an accepted and popular design was for all (or most) pump discharges and line gauges to be in a single row. Some manufacturers actually determined the width of pump houses by the number of gauges to be put in a row! Today, the trend is to squish everything into as tight an envelope as possible. Many operator panels have become a hodgepodge of crammed-in gauges and controls with no apparent logical sequence or layout. The rig in photo 7 is an exception.

Photo 7 shows a very busy but well-laid-out 45-inch wide panel on an equally well laid-out pumper (or engine). Regardless of whether by customer request, the manufacturer’s design, the available space to mechanically lay things out, or a combination of all three, it appears user friendly for everything that’s on it. A nice job.

From the perspective of firefighter safety and ease-of-operation, those concerns are addressed first. I do not believe discharges of any size, auxiliary suctions, or gated LDH connections should be on any operator’s panel nor should preconnected hoselines be allowed above or immediately next to the pump operator’s head. It’s not safe. Its unwise to have high pressure connections next to one’s cranium, knee caps, or private body parts. Open hose troughs should not be permitted where firefighters have to stand to reload crosslays. It is a tripping hazard. Find another place to put the hose and provide a slide-out step to facilitate hose loading crosslays.

The good stuff on this panel include six-inch master gauges and 3½-inch line gauges—both limited to 400-psi readings—that are easy to see and read. All the basic pump controls are located from waist to mostly chest and eye level—easy to access. It appears the manual handwheel controllers were sized to meet the three-inch and four-inch discharge valve sizes. The push-pull tank-to-pump controller is configured so in is open and out is closed. It looks like they run with a wet pump, which saves one step in securing tank water. The pull rod control handles for all preconnected lines have the size and length of the hose inscribed on the handle. Despite having nine discharges, a panel-controlled rear LDH connection, onboard foam with a panel-mounted fill connection, all the required labels and gauges, and the two overhead crosslays, the only electrically operated valve necessary is the one for the rear LDH suction. Somebody put some effort into designing the layout.

In later reviewing these photos, it appeared the purchaser had added several stickers to some of the discharge gauges: 80 PSI, 103 SB, 85 SB and 117 AM. There was no problem understanding 80-psi on the discharge gauge but I couldn’t figure out what SB and AM meant. I contacted the fire chief who straightened me out—smoothbore and automatic nozzle. You learn something new every day.

On a slide-out tray in this pump operator’s compartment are items seldom seen carried anymore. One is the Akron No. 0535 2½-inch 250-gpm cellar nozzle, which according to Akron’s catalog has “9 variable angle orifices: (3) 3/8-inch and (6) 13/32-inch and meets Insurance Services Office (ISO) requirements.” The catalog’s statement of “for attacking fires in hard-to-reach places” is interesting. How often are cellar nozzles used? How often do departments train with them?

There’s also a Harrington HWS-25NH 2½-inch Water Shield. It flows 370 gpm and projects a pattern 78 feet wide by 26 feet high. I haven’t seen a new one in years and wish I’d asked the firefighters how often its used.

There’s a lot of loose equipment carried on these three pull-out shelves. Although having each piece of equipment mounted may look good and in many cases is functional, there may not physically be enough room to do so in the space allotted. Additionally, a department may want the flexibility to move equipment around and to add or delete the same after having actual experience in the field.

The local and regional trade shows are excellent forums for observing apparatus destined for local departments. And, more than likely, the owners of these new rigs will be hovering nearby ready to answer questions. These observations are not denigrating the time, effort, and expense put forth by the manufacturers and their factory personnel at national trade shows. Both have their place.

BILL ADAMS is a member of the Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment Editorial Advisory Board, a former fire apparatus salesman, and a past chief of the East Rochester (NY) Fire Department. He has 50 years of experience in the volunteer fire service.